Although ever the dutiful son, he was an absent father to his daughter Jan, even denying his paternity. He advocated freedom, abandonment of responsibility, heading out into the mystic night of a magical America where the land bulged on the horizon into infinity, yet he never cut the apron strings, eventually dying while living with his mother. Brought up a Catholic, he adopted a cherry-picked hybrid Buddhist spirituality, shot through with grief after the death of his older brother Gerard, aged just nine, who Kerouac revered as a saint. It’s Kerouac’s complex life, his contradictory views, his duality in so many things, that gives him more cachet than ever. Here I am, arguing that Kerouac is more relevant than ever as we mark 100 years since his birth. The consensus seems to be that Kerouac is a thing for callow youths, to be grown out of, to be reassessed in maturity and found wanting.Īnd yet, here I am, more distance now between here and my visit to Kerouac’s grave than there was between me standing in the scorching July heat looking at the flat gravestone bearing his childhood nickname Ti Jean in Edson cemetery and Kerouac’s death in Florida. Kerouac’s works often make it on to lists of red-flag books that, if you see on the shelf of a man you are dating, you should run a mile.

The same year saw the BBC TV adaptation of Hanif Kureishi’s 1990 novel, The Buddha of Suburbia, in which social climber Eva chides protagonist Karim for reading Kerouac, quoting Truman Capote’s dismissive “that’s not writing, it’s typing”, and opining, “The cruellest thing you can do to Kerouac is re-read him at 38.”

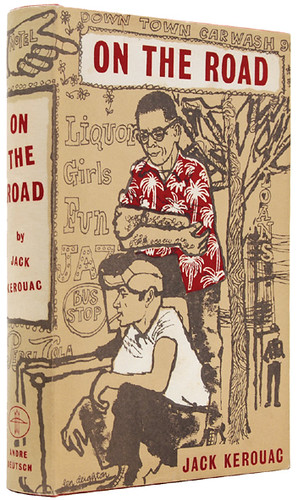

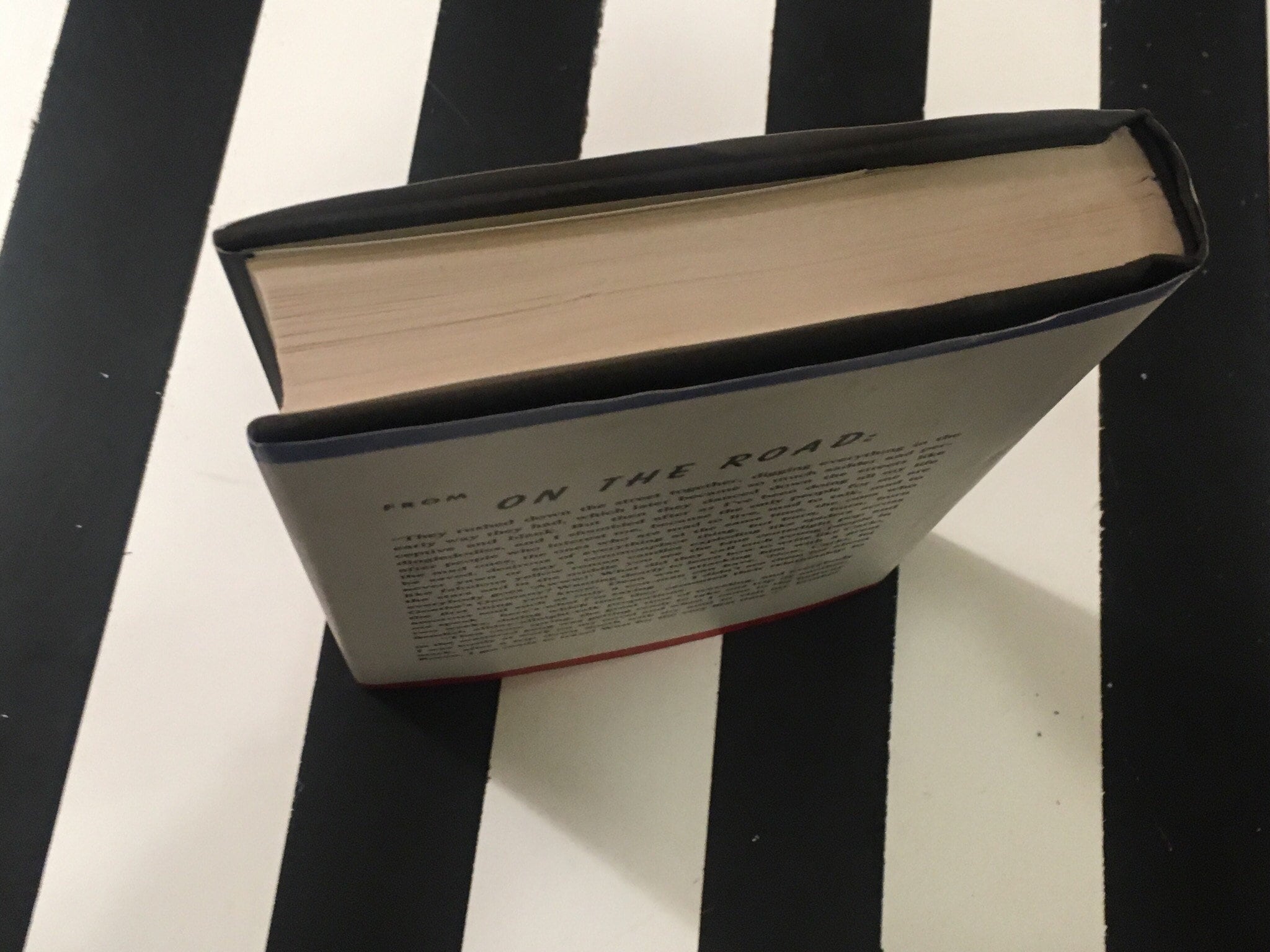

In 1993, midway between me discovering On The Road aged 21 and going to visit Kerouac’s birthplace, Gap used him in an advertising campaign to sell their khaki trousers. Kerouac seems equally revered and despised, for his jazz-infused spontaneous prose largely plotless novels, for his often contradictory lifestyle. Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel On the Road is an American classic.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)